Calton Hill, like Arthur’s Seat, or Castle Hill, has always just ‘been there’ through my life, almost taken for granted. I don’t recall the first time I climbed the hill, it was probably when I was quite young. I’ve recently been re-discovering its attractions and reading about its eventful past. You sense this history as you ascend the hill and survey the surrounding area, even more so than on Blackford Hill, still my personal favourite of the so-called Seven Hills of Edinburgh. This is the first of two posts about Calton Hill and the buildings and monuments adorning its slopes.

Calton Hill is an easy climb coming from the East end of Princes Street, or from Regent Road. Once you’re at the top, there are spectacular views in every direction, extending to Fife in the North, North Berwick, Bass Rock, and the Law to the East, the Pentland Hills to the South, and looking West, the bridges spanning the Forth are clearly visible on a good day.

I recently bought Robert Louis Stevenson’s book about Edinburgh, which is full of wit and is very readable despite being published in 1878. He talks at some length about Calton Hill.

Of all places for a view, this Calton Hill is perhaps the best; since you can see the Castle, which you lose from the Castle, and Arthur’s Seat, which you cannot see from Arthur’s Seat.

Robert Louis Stevenson – “Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes” (1878)

Calton Hill is a photographer’s dream location, as evidenced by the sheer number of photos taken here over the years. Notable is the famous view looking West past the Stewart Monument out to Princes Street, the Balmoral Hotel, and the Scott Monument. The photo above is my version of this view as a sunset, it’s hard to avoid pointing your camera in that direction, as countless hundreds have before me.

The hill was one of the first public parks in Scotland and remains popular with walkers and tourists. It’s been the focal point of writers, artists, astronomers, geologists, and photographers. It’s also hosted a jail (see Part 2), a monastery, and a leper colony. Witches were burned and jousting tournaments were held in the gully below. It’s a symbol of national identity and cultural significance and is part of UNESCO’s Edinburgh World Heritage Site. Not bad for a relatively small area of the city and reaching a mere 103 metres in height.

A Brief History

Formation and Geology

Calton Hill was formed from volcanic activity around 300 – 350 million years ago, part of an active volcano complex called The Arthur’s Seat Volcano. The same geological forces that shaped Castle Rock, and the nearby hill called Arthur’s Seat, also created Calton Hill. The hill is thought to be a fragment from the cone of the Arthur’s Seat vent.

Not being a geologist, I was interested to read that Calton Hill is a ‘crag and tail,’ a result of the last ice age. Thick ice sheets covered Edinburgh and moved from West to East. Features of this geological formation are steep cliffs around the West side of the hill worn down by the ice, and long gently sloping tails to the East, in the wake of the ice flow. Blackford Hill is also a crag and tail, and Edinburgh Castle Rock is a crag, with the Royal Mile forming its tail.

What’s in a Name?

Craigingalt was the earliest known name of Calton Hill, dating from 1456, and it means ‘on the hill or wooded hillside’. Curious about the origin of the name Calton, my limited research threw up the Scots Gaelic name Calltuin (meaning ‘hazel grove’) and was widely used by locals. This then developed through several variants such as Cauldtoun, finally becoming Calton in the 18th century.

Monuments and Buildings

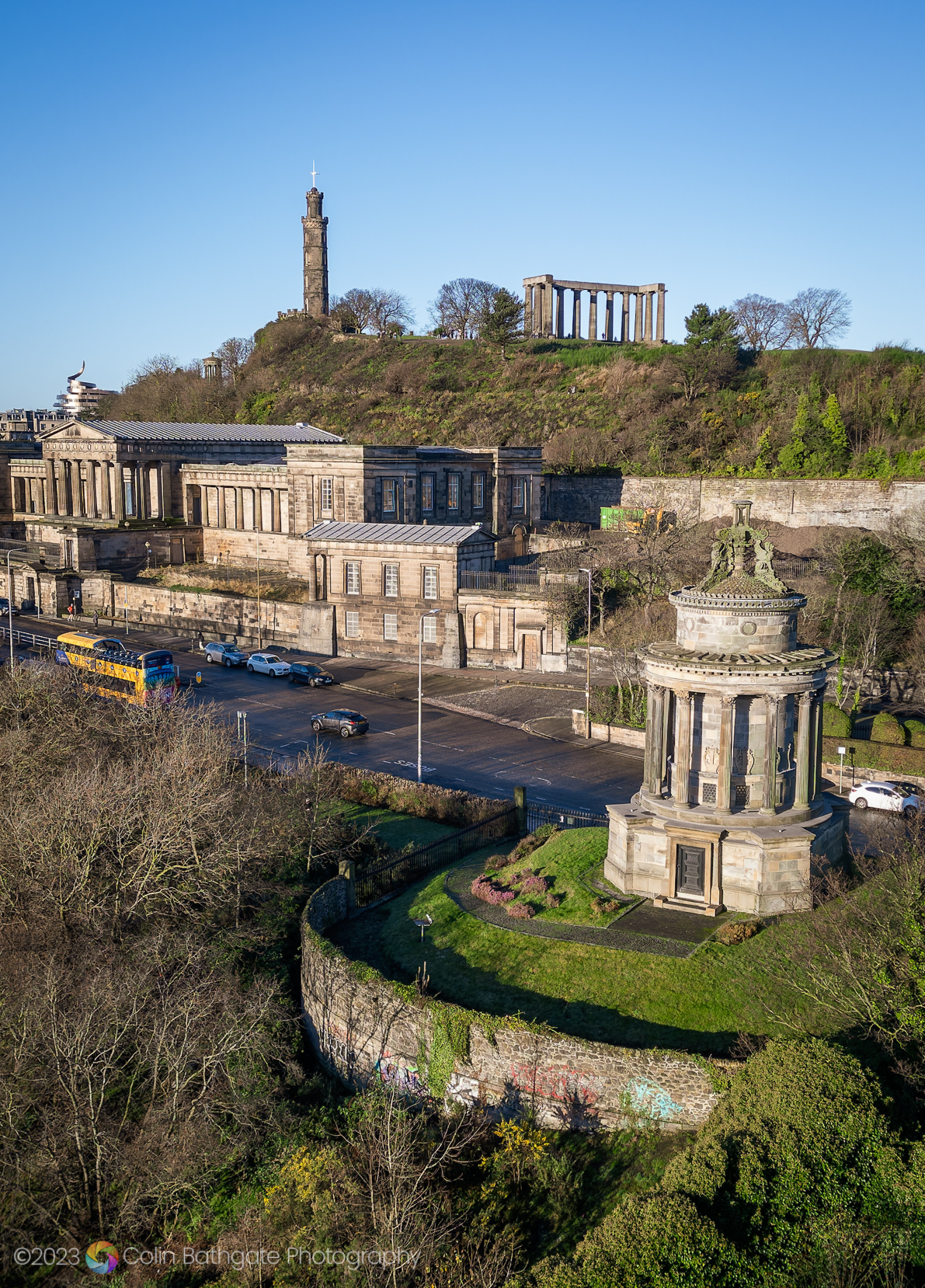

The National Monument

Possibly the most striking structure on the hill is formed from twelve neo-classical columns, resembling the Parthenon in Athens. These are made from sandstone from Craigleith Quarry, which also provided building stone for most of the New Town. The monument commemorates the Scottish soldiers who fought and died in the Napoleonic Wars.

The design was by two of the most notable architects of the day, Englishman Charles Cockerell and Scotsman William Playfair. Construction started in 1826 but the monument was left unfinished in 1829 when money ran out. The monument’s incomplete state led to its nickname ‘Edinburgh’s Disgrace’. Regardless of the politics which led to its commission, most residents and visitors now accept the monument in its incomplete state.

It’s a much loved part of the Edinburgh landscape, visible for miles around. When I’ve been there, it’s been amusing to watch tourists and other visitors climbing onto the base and having their photo taken, a light hearted contrast with the serious minded cultural ideals that led to its commission.

The Nelson Monument

Perched like a lighthouse on the crest of Calton Hill, stands another landmark in Edinburgh’s skyline – The Nelson Monument. Rising 32 metres above the city, its silhouette echoes an upturned telescope. It’s a structure that can divide people. It’s either a fitting tribute to Admiral Horatio Nelson’s naval prowess, or as Stevenson put it:

…it ranks among the vilest of men’s handiworks.

Robert Louis Stevenson – “Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes” (1878)

It’s not clear if Stevenson’s objection was political or aesthetic, but I have to admit I hadn’t realised until recently that it was designed to look like a telescope. Sadly, at time of writing it’s not possible to climb the 143 steps to the top, but from previous visits I can tell you that the views across Edinburgh are worth the effort should it ever re-open to the public.

Architect Robert Burn designed the structure, and building began in 1807, but money ran out the following year. Burn died in 1815 (he’s buried, appropriately enough, in Old Calton Burial Ground), and it was left to Thomas Bonnar to complete the base to the tower, finishing in 1816.

On top of the tower is a time ball, a large wooden ball with an outer shell of zinc, raised and lowered to mark the time. It became operational 1854, allowing ships in the Port of Leith and in the Firth of Forth to set their chronometers. The time ball was the idea of Charles Piazzi Smyth, who was Astronomer Royal for Scotland, and was originally triggered by a clock in the adjacent City Observatory, to which it was connected by an underground wire. Later, the One O’clock Gun was established at Edinburgh Castle and provided an audible signal when fog made it impossible to see the ball.

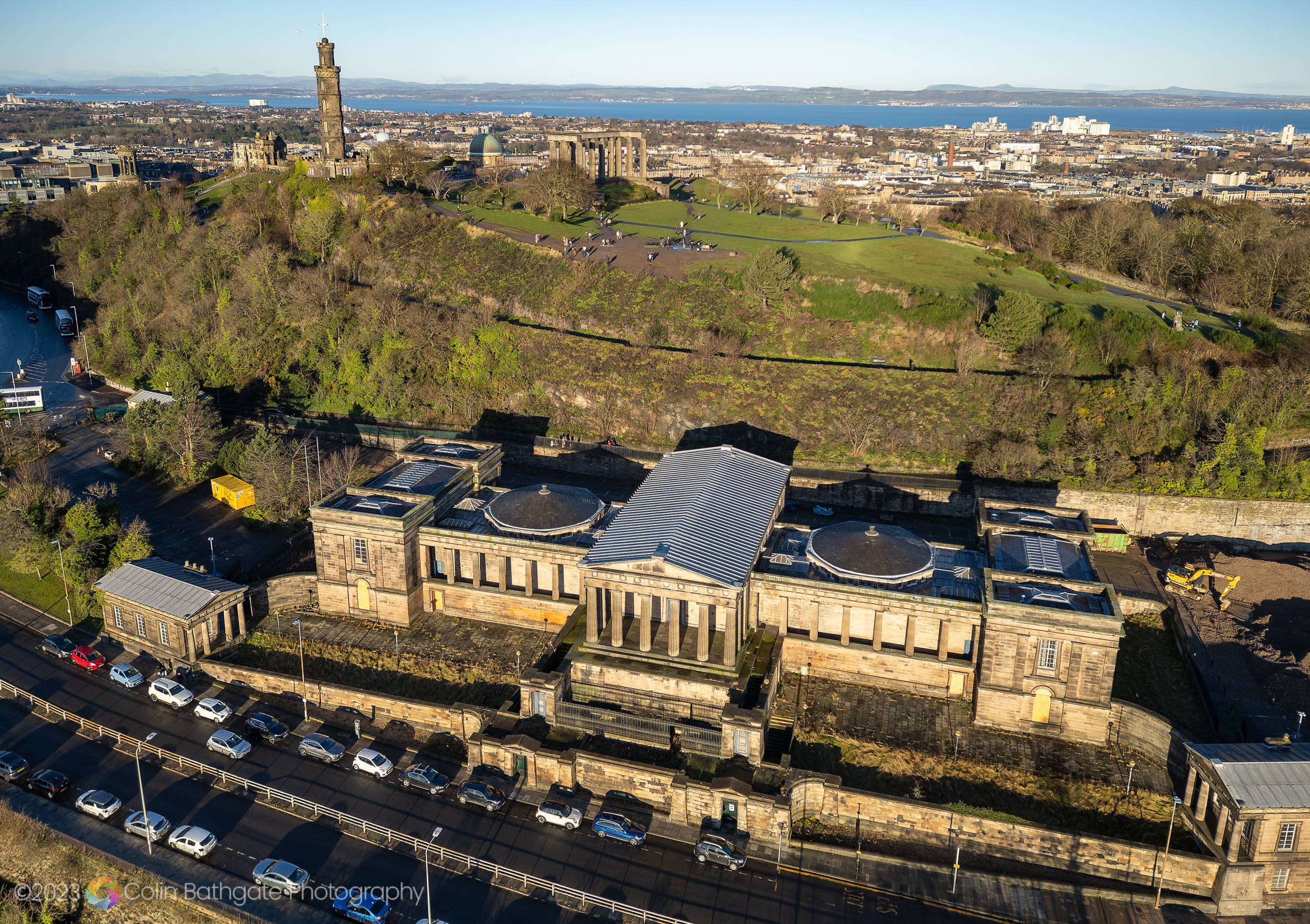

The Playfair Observatory

Calton Hill is the birthplace of astronomy in Edinburgh, the oldest surviving building being the gothic tower which now forms part of Observatory House. This remnant marks the initial attempt to build an observatory on the Hill in the 1770s. The Playfair Observatory, designed by the renowned Scottish architect William Henry Playfair, was completed in 1822. The Observatory is also known as the City Observatory, or Calton Hill Observatory, and follows a neoclassical design, with symmetrical wings extending from a central dome.

The main telescope’s housing features a ‘transit’ slot in the ceiling, aligned with the local meridian line, allowing astronomers to observe stars and maintain the accuracy of the observatory clock. When the time ball was installed on the nearby Nelson’s Monument (see above), electrical pulses from the Observatory clock operated the dropping of the ball at precisely 1pm.

In the aerial photo above, you can clearly see the cross plan of the Playfair Observatory in the centre. Top left corner is the Playfair monument, top right corner is Observatory House, bottom left corner is the City Dome, and bottom right corner a new restaurant called The Lookout.

The large green dome, the City Dome, was added in 1895, and was designed to house a telescope with a 22-inch lens, too big for Playfair’s observatory.

After the Royal Observatory relocated to Blackford Hill in 1896, the original observatory fell into disrepair, with its lead roof stolen and its interiors succumbing to rot. After a multi million pound restoration completed in 2018, the observatory became part of the Collective contemporary art space, hosting exhibitions and events.

Dugald Stewart Monument

The Dugald Stewart Monument is one of the key structures on Calton Hill that helped to earn Edinburgh the nickname ‘Athens of the North’. The monument is a memorial to the Scottish philosopher Dugald Stewart (1753–1828). Completed in 1831 to a design by William Henry Playfair, the monument is modelled on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens.

I have to admit I didn’t know much about Dugald Stewart (in other words, I knew nothing about Dugald Stewart), and why he merits such a prominent place on Edinburgh’s skyline. Consider that Robert Burns’ monument is much further down the hill, though he admittedly isn’t an Edinburgh man (it’s also notable that all the monuments are to men, but that’s not specific to Calton Hill).

Dugald Stewart was a mathematician and philosopher, and his reputation was made during the Scottish Enlightenment, a time when Scotland’s intellectual and scientific accomplishments flourished. Stewart held the chair of moral philosophy at the University of Edinburgh from 1786 until his death.

Stewart had a huge impact on the intellectual climate of his time, through his lectures and his writings. The Royal Society of Edinburgh commissioned the monument and selected its site in 1830, and Edinburgh University named the Dugald Stewart Building in his honour, home to the university’s School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences.

The Spanish Cannon

This well travelled cannon placed between the Nelson Monument and the Playfair Observatory has a long and complicated past.

Known as the ‘Portuguese Cannon’, this artillery piece bears a Spanish royal coat of arms. Made in the 1400s, it travelled from Spain to Portugal’s Asian colonies, then to Burma. It was captured by the British during the invasion of Burma and presented to Edinburgh in 1886.

Did you know there used to be six cannons on Calton Hill? In 1940 the other five were melted down for metal during World War 2.

The Burns Monument

Re-opened in 2009 following extensive restoration work, this is a small, circular temple in the neo-Greek style, constructed in honour of Scotland’s national bard Robert Burns.

The monument is on Regent Road at the Southerly foot of Calton Hill overlooking the Canongate Churchyard. Robert Louise Stevenson again has interesting thoughts about the vagaries of fame.

The scene suggests reflections on fame and on man’s injustice to the dead. You see Dugald Stewart rather more handsomely commemorated than Burns. Immediately below, in the Canongate churchyard, lies Robert Fergusson, Burns’s master in his art, who died insane while yet a stripling; and if Dugald Stewart has been somewhat too boisterously acclaimed, the Edinburgh poet, on the other hand, is most unrighteously forgotten.

Robert Louis Stevenson – “Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes” (1878)

The idea to erect a monument to Burns was first proposed in 1812. Architect Thomas Hamilton, known for designing the Burns Monument at Alloway and the nearby Royal High School, was appointed for the project. Construction began in 1831.

The monument, built in Ravelston sandstone, is capped with a domed roof, with intricate stone carvings and winged lion sculptures. A white marble statue of the poet was originally housed in the monument but this was moved to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery due to damage from the city’s gas works.

Old Royal High School

The Old Royal High School is a 19th-century building on Calton Hill. The A-listed building was constructed in 1829 for the use of the city’s Royal High School. This is another neo-classical design, this time by Thomas Hamilton.

The building became available after the school relocated to larger modern premises at Barnton in 1968. It was subsequently refurbished to accommodate a new devolved legislature for Scotland. However, the 1979 devolution referendum failed to provide sufficient backing for a devolved assembly.

A number of proposals for the school have fallen by the wayside. These have included plans to move the Scottish Assembly into the building in the 1970s, and a more recent scheme for a £20 million National Photography Centre.

With the passage of the Scotland Act 1998 and the introduction of Scottish devolution in 1999, the Old Royal High School was again suggested as a home for the new Scottish Parliament. Eventually, however, the Scotland Office decided to site the new legislature in a purpose-built building opposite Holyrood Palace.

Submitted in response to the council’s search for a long-term use for the old Royal High School, the Royal High School Preservation Trust (RHSPT) have proposed that the building be turned into a new National Centre for Music. This will comprise a 300-seat concert hall, with new public gardens, and a restaurant.

This completes Part 1, the next post, imaginatively entitled ‘Part 2’, will follow.